Facilitated Communication: What’s the Controversy?

What is Facilitated Communication?

Facilitated communication, or FC, is a discredited and controversial communication technique.

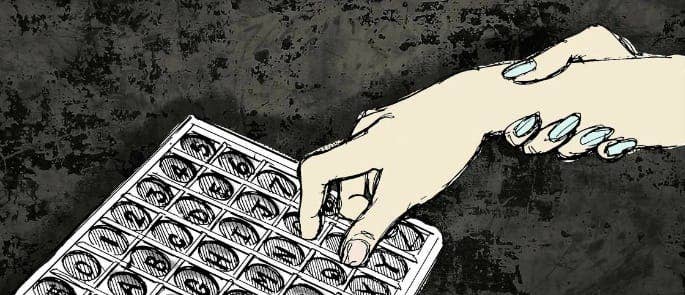

It involves a tutor “aiding” a person with communication (often someone with autism or a developmental disability). During facilitated communication, a “facilitator” acts as a physical writing aid. They support users by guiding their movements to help them point at pictures or type on a keyboard. The support ranges from guiding someone from the wrist, elbow or arm to guiding their hand or finger.

Its supporters package it as a miracle communication method. They claim that it gives a voice to people with severe communication impairments and people with developmental and cognitive disabilities.

But study after study shows it just doesn’t work.

However, despite being discredited and highly controversial, FC has survived. There’s a small but vocal section of society who are behind the resurgence of FC in disability and education settings. Using a deliberate and strategic rebranding, these advocates renamed FC under guises like “supported typing” and the “Rapid Prompting Method”. This was an attempt to make the practice appear more scientific and to escape the controversy.

It’s an ethical duty to end FC and push for access to genuine methods of communication.

Source: Skeptic

When did the FC controversy begin?

In the 1990’s, FC was at the height of its popularity. The movement gained traction amongst educators in Australia in the 1970’s and 80’s. And it soon spread to America and other parts of the world such as Canada, France, Austria, the UK and Finland.

Suddenly, autistic people who had never spoken were communicating in fluent and creative ways. It was a miracle for educators and families.

Why is it so controversial?

The big problem with FC is that the facilitator becomes a ventriloquist.

Study after study shows that facilitators influence and control what their users say. And this makes facilitated communication all the more dangerous.

Despite the irrefutable evidence, professionals and so-called “FC experts” refuse to accept that they’re influencing the person they want to help. This is understandable; the heart of FC supporters is often in the right place, but their advocacy is unethical and dangerous.

It’s not just that FC doesn’t work, it facilitates abuse.

For example, FC has enabled the abuse and manipulation of many vulnerable people by facilitators. The high profile cases of Anna Stubblefield and the Wendrow Family demonstrate how FC ruins lives.

Source: Skeptic

Case Study: The Wendrow Family

In 2007, the Wendrow family were wrongfully prosecuted for sexual abuse allegations made via FC. Aislinn Wendrow was diagnosed with non-communicative autism at age two and began using FC at school with a teaching assistant. At 14, Aislinn typed out messages that claimed her father had repeatedly raped her while her mother ignored the abuse.

The case was dropped months later. During the trial, it was repeatedly shown that Aislinn could not type correct answers if her facilitator had not heard the question that she was asked. During this time, her father spent 80 days in jail, and the family was devastated by the case and allegations.

Case Study: Anna Stubblefield

Anna Stubblefield is a former chairwoman of the philosophy department at Rutgers University, a mother of two, and a disability rights activist. Last year she was found guilty of raping a 31-year-old man called DJ with cerebral palsy and severe cognitive disabilities.

DJ’s brother had been taught by Stubblefield at university. With good intentions, he arranged a series of meetings to see if Anna could help DJ communicate through FC. DJ’s family wanted facilitated communication to work, and their desire was a powerful force.

In 2011, Anna told DJ’s family that they were in love and that he had consented to a sexual relationship through facilitated communication. DJ’s family were distraught. When they found out what happened, their desire to see DJ communicate was overtaken by a protective desire to stand up for his voice and rights, and the very ugly side of FC came to light.

Anna had manipulated their trust and their hopes.

Source: New York Times

The judge sentenced Anna to 12 years in prison for the rape of DJ. But debate still thrives over the sentencing and whether the trial was fair. Some of this is from FC supporters, who claim FC remains valid and that it’s unfair to expect users to perform under trial pressure.

But most of the debates arise because DJ was left out of the trial; his cognitive abilities were not reassessed, and he was presumed to be incompetent. He was also denied access to other legitimate and valid forms of communication that could have helped him testify if it was determined he had sufficient cognitive ability. These debates assert DJ was overlooked and that adequate measures were not taken to understand DJ’s abilities.

What have we learned from these case studies?

Both these cases should be damning enough to lay FC to rest, but seemingly not.

Supporters of the FC movement continue to advocate for it, including Stubblefield who recently claimed that taking a position against FC is “hate speech”.

Advocates of FC, purposefully or not, encourage doubt and controversy. But this allows abuse to continue; it’s the seeds of doubt that exploits the hope of families like the Wendrow’s. There are far too many people in positions of power who claim that FC works for some and all this evidence, however convincing, remains anecdotal.

As much as we can want a thing to work, there has to be a point where we accept that it just doesn’t.

With FC, the stakes are too high and the abuses too many to believe blindly in its value.

Source: Slate

Need a Training Course?

Our Autism Awareness Training will help you understand more about Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASDs) to recognise the challenges that autistic children face so that you can help them reach their full potential.

FC Deprives Autistic People of a Genuine Voice

Jeffrey Chan and Karen Nankervis point out that FC exposes people to exploitation and those “facilitated” are not actively involved in any decision-making processes. The authors also demonstrate that FC conflicts with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. This states that when using AAC methods, users should be “free from exploitation and for the person to be actively involved in the decision-making process.”

This is not the case with facilitated communication, making it an abuse of human rights.

Because of this, FC breaches the right for people with disabilities to access legitimate ways of communication. Which leads to the next controversy: FC denies non-communicative autistic people a voice through which they can express themselves.

Augmentative and authentic communication methods (or AAC) are techniques of communication other than oral speech that facilitate expression. They include all forms of communication that express thoughts, needs, wants, and ideas such as unaided communication systems. These may be facial expressions, gestures, body language and sign language, as well as aided communication systems such as writing, electronic communication aids or symbols and pictures.

Genuine AAC methods are vital for giving freedom and choice to people with severe speech or language problems. Unauthentic methods like facilitated communication do the opposite. They, in effect, “steal” the voices of disabled citizens, breaching the UN Convention on disability rights that says people have the “right to communicate through valid augmentative and alternative communication methods.” The imperative word being valid.

At the moment, there seems to be no end in sight to the many faces of FC. To end detrimental practices and beliefs such as the autism-vaccination myth and facilitated communication we need a united front by all in healthcare, education, and disability rights.

These practices and beliefs are not harmless; they can ruin lives.

Further Resources:

- Autism Awareness Quiz

- Female Autism: Is it Different and What Should I Look Out For?

- Communication Skills Quiz

- Autism Awareness Course